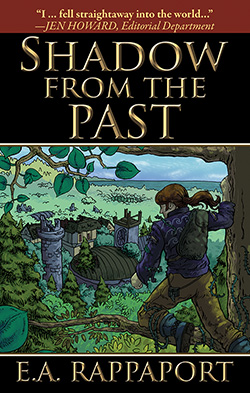

Shadow from the Past - Chapter 1

Cassor approached the Gathering Tree, a massive banyan dominating the center of Hillswood. Its outer branches streamed down from the sky a hundred paces from the trunk, forming a natural dome beneath which many adult Arboreals conducted their business while the younger tenderlings attended their studies. On his way toward the old banyan, Cassor passed several groups of workers. Pollinators selected the perfect seeds to plant, germinators ensured that the seeds sprouted properly, and feeders gave the seedlings the proper amount of nutrients. Climbing through the thousands of branches above him were healers, pruners, and scores of other Arboreals dedicated to the sylvan life cycle.

Unlike the majority of his fellow townsfolk, Cassor carried a slender sword by his side. Since he’d become an elder, however, he found little use for the weapon. The last time he’d held the blade in combat was several springs ago, when he’d scared away a young sabertooth that had wandered into Arboreal territory. Too many people took the current span of peace for granted.

He reached the Gathering Tree and scaled the trunk as easily as a stroll across a moss-lined forest path. Near the top of the tree the branches parted into a doorway, revealing a circular chamber hidden within the crown. Uncountable branches packed with firm green leaves formed the floor, ceiling, and walls of the room in addition to a table and six chairs.

“At least I’m not the first to arrive,” he said as he entered the room.

One of the younger members of the elder council, Cassor wore his long green hair in a braid and always dressed in a sleeveless tunic. He proudly displayed a scar, running from his shoulder to his wrist, that he’d received during a bloody battle of the Brymorian War. Stronger than most Arboreals because of his training, his body resembled that of a Ferfolk, stocky and muscular but without the leathery skin.

Cassor breathed in the sweet smell of nectar. “Isn’t it too early for the honeysuckle to bloom?”

Long flowering vines weaved in and out of the branches, adding a pattern of yellow and white to the room’s perimeter.

“It is a bit early,” said Kuril in a weathered voice, “but the caretakers coaxed them from their buds for me. After all these springs, I’m still not comfortable with these drab northern winters.”

Looking extremely old, Kuril sat in a branch chair at the head of the table. Even after a half-century, he fingered the long scar on his cheek, now withered with age. His baggy clothing made him appear more wrinkled than he was, but a heavy gold chain strapped to his waist enhanced his otherwise dull outfit.

Cassor scowled at the belt. Metal was good for weapons and nothing else.

Beside Kuril, Eslinor sat motionless. With a narrow face and a delicate smile, her beauty was unrivaled in the entire hamlet. Her olive hair, twice as long as Cassor’s, flowed down her back and mingled with the leaves of the chamber floor. She draped her mottled green dress over the sides of her chair, making it appear as if she were part of the furniture.

The final elder present, Aquila, had dark skin and was dressed in brown clothes, appropriate for working in the dirt. A trio of brightly colored feathers held her hair firmly in a bun, except for a handful of long strands flowing over her shoulder. Aquila held the loose strands in one hand and ran her fingers through them. She tilted her head toward an empty chair and raised her eyebrows.

“Isn’t it noon already?” asked Cassor, disdaining the customary wordless communication of nods and gestures. “I don’t feel like waiting for the others. Let’s begin without them. Polsor and Zehuti can join us whenever.”

“Be patient,” said Kuril. “Sit and meditate with us on this beautiful morning. The others will arrive soon enough.”

“Soon enough for what?” asked Polsor as he stepped into the room and nudged Cassor aside.

“Do you still refuse to straighten your hair?” asked Cassor.

He wanted to comment about the similarities between Polsor and a wild human, but that would only delay things further.

“It’s not yet the equinox,” said Polsor, a near twin of Cassor except for the top of his head. He shook his tangled mass of shoulder-length hair and gazed around the room. “Good, Zehuti isn’t here. Shall we begin without him?”

“Just because we disagree with his research doesn’t mean we should exclude him from our discussions,” said Aquila.

“It’s not only his research,” said Polsor. “He always gets his way, whether allowing others to live among us or stopping our trees from going north. Don’t we have an equal say in the matter?”

“Perhaps you’re not persuasive enough,” said Cassor, slapping his brother on the back. “You should take lessons from your grandson.”

Behind them the leaves rustled as Zehuti appeared. An older Arboreal with a youthful appearance, Zehuti had dark green eyes, an unusually hefty build, and a shaved head. He pushed his way past the much taller brothers.

“I have a request,” he said.

“If you were so anxious to begin,” said Cassor, “you shouldn’t have come late.”

“I apologize, but I was in the middle of an experiment that took me a fortnight to prepare. Unfortunately, I’m still missing a key element.”

Polsor glared at him. “Why don’t you give up these frivolous experiments? They’re pointless.”

“Or move closer to the Gathering Tree,” said Cassor, sitting beside Aquila. “The northern spiral is too far from the center of town for an elder.”

Zehuti shook his head with an almost-frightened look on his face.

“No one has to move their home,” said Polsor, in rare agreement with the old Arboreal. “We’re all here now and the sun has only just peaked. Shall we begin? I believe Zehuti has a request for us to agree upon.”

Kuril gave an almost-imperceptible nod, echoed by Aquila and Eslinor. Cassor, however, smiled at his brother’s sarcasm. Whenever Polsor was upset, he’d always brighten his mood with a joke or a lighthearted comment.

Zehuti spent a few extra moments getting comfortable in his seat across from Kuril. “My research has kept me busy these past springs. I’ve even asked my wife, Otha, to assist me on occasion. The humans had known more about magic than we’d imagined.”

“That’s impossible.” Polsor chuckled. “The humans would have been lucky to gain a fraction of our knowledge during their short lives. They were marginally more intelligent than the spider monkeys that frolic outside of town.”

“Don’t have such a closed mind,” said Zehuti. “Each one of them might have lacked our wisdom, but as a group, they held much knowledge.”

“What the humans knew was concentrated on destructive behavior,” said Cassor. “They spent their few springs exploiting fire, imprisoning spirits and animals, and creating ever more dangerous weapons. We shouldn’t concern ourselves with such pursuits.”

“Most of their efforts were indeed spent on subjects we choose to avoid,” said Zehuti, “but that doesn’t mean they were as ignorant as you say. Some of their knowledge might aid us in our own specialties.”

Cassor joined his brother in laughter. He’d known several humans, and none had ever approached the experience or wisdom of an Arboreal. Kuril, Eslinor, and Aquila grinned slightly, adding their equivalent of a hearty laugh.

“Don’t mock me until you’ve seen the results of my research,” said Zehuti. He touched the leaves on the floor and whispered a few words.

An old Arboreal entered the room carrying six tomes wrapped in brown leaves. Otha had long braids of gray hair, heavily wrinkled skin, and a warm face. She could have been mistaken for Zehuti’s mother instead of his wife. Without a sound, she placed the set of books by Kuril’s feet and left the chamber.

“These observations are only the beginning of what I’ve discovered,” said Zehuti. “I need an apprentice to work with me and continue my research should anything prevent my involvement in the future.”

“You’ve already spent too much of your own time on this wasted research,” said Cassor. “We shouldn’t squander the talents of our tenderlings as well. It would be more helpful to train them in swordplay. Each spring there are fewer guardians. Just because the Ferfolk haven’t attacked us recently doesn’t mean they’ve given up their aggressive nature. Should we forget their vicious forays against us during the war? They killed innocent animals, burnt down hamlets, and trampled every living plant in their path.”

“We haven’t seen a Ferfolk for the past twenty springs,” said Aquila, “and I don’t expect this one to be any different.”

Zehuti glanced at her, lifted the top book off the pile, and placed it on the table in front of Cassor. “Please keep an open mind.”

Cassor crossed his arms. His brother was correct. The others would follow whatever Zehuti suggested, regardless if it were best for the hamlet.

“Just because we’ve had a few springs of peace doesn’t mean we can trust the Ferfolk,” he said. “They’re a race of warriors. The best time to attack is when your enemy least suspects danger.”

“Are you suggesting we attack them?” asked Aquila.

Eslinor’s face curled up in horror. “That would be terrible. We’re a peaceful people.”

“I suggested no such thing,” said Cassor. “If we don’t prepare to defend ourselves, the Ferfolk would have an overwhelming advantage.”

With a quick sneer at Zehuti, Polsor nodded. “We should get our tenderlings ready for war. Many of them have never touched a sword.”

Cassor stifled a grin. He appreciated the support, but his brother cared more about pestering Zehuti than about weapons training. Polsor hadn’t picked up a sword in many springs.

“We seem to be split on this matter,” said Polsor, turning to Kuril. “What do you say?”

Kuril’s eyes shifted downward for several minutes before returning to the group with a silent answer, expressed by a quick gaze at the books and a nod at each of the elders. Cassor cocked his head at his brother. It was just as he’d predicted.

“You’ve made a wise suggestion, Kuril,” said Eslinor. “We’ll review Zehuti’s findings in detail before deciding either of these issues. Should his research merit additional effort, I have just the tenderling to make a fine apprentice: the orphan Jarlen.”

“He’s not even a full Arboreal,” said Cassor, quieting when Kuril scowled at him. Polsor would have agreed, but the others were united against them.

“Good now,” he said. “I’ll read Zehuti’s work, but we must speak further about the Ferfolk before adjourning.”

Zehuti passed out the heavy tomes.

“Our treaty with the Ferfolk has been sufficient in the past,” he said, “but we have several hours before midnight arrives. There’s always the possibility of danger, and one can never be too safe.”

When the morning sun roused Petula from her meditation, she climbed through the ceiling of her sleeping chamber, past her well-stocked dining area, and into a special garden at the top of her mahogany tree. Rays of sunlight filtered into the room, nourishing scores of herb and vegetable plants. It had rained overnight, and any water that hadn’t found its way to the soil in one of the many leaf planters followed grooves in a few specially grown branches, spilling out at the base of the mahogany.

Petula sang to her plants for an hour, after which she dug up root vegetables, harvested edible leaves, and collected drops of nectar from the flowers. She cared for each member of the garden and then sank through the floor to the dining area. While humming to herself, she prepared a meal of diced figs, crunchy vegetables, and sweetened greens.

Soon she had a table full of food, two place settings, and no husband in sight.

“It’s time to end your meditation,” she called out. “Why must you always rise late?”

She caressed the branches of the eastern wall and sang a soft tune. Below her feet, the tree limbs rustled gently.

“Is it morning?” a groggy voice responded.

“Dawn has long since passed and it’s time to eat,” said Petula. “I’m not waiting any longer.”

“You sound like a human,” said the voice, “always rushing me.”

“If you’re going to insult me,” said Petula, “you can eat when you want. I’m hungry now.”

She rearranged the plates, each one made from overlapping leaves covered by a thin layer of wax. After waiting a few more minutes, she finished her breakfast in leisure.

“Don’t skip your morning meal,” she said when she was done, “or you’ll be hungry all day.”

Petula touched the northern wall of the chamber, causing an opening to appear in the branches. She stepped outside onto a large limb overlooking a swamp. Below her pools of water glistened in the sunlight, offering her no room for a ground-level garden. The house stood at the tip of the southern spiral, surrounded on three sides by an immense swamp.

She crawled northward through the canopy along a treetop passageway. Branches from neighboring trees clasped one another, forming a nearly continuous path high above the ground. When she came to a rare break in the path, she chanted a brief song, causing the tree limbs to extend outward, weave together, and patch the hole.

Petula halted after climbing through several trees, her eyes drawn to the ground. The end of an oddly shaped black stick was poking up through the muddy water. She leapt down without a sound and circled the strange object, viewing it from all angles. Deciding there was no danger, she leaned in for a closer look.

The stick was the top of an ornate staff buried in the muck. A pair of intertwined snakes formed the shaft with their heads pointed away from each other and their tongues extended. Petula poked the wood a few times and yanked it from the water. She fell backward when the staff, missing the lower section, was only half as long as she’d expected. She plunged her arm into the murky water but found nothing else.

Petula wiped the mud from her clothing, staring at the old staff. The quality of the carving seemed Arboreal, but only humans would have defiled wood. They always liked serpents and other unappealing beasts.

“I should throw you back to your watery grave.”

She raised the staff behind her shoulder, ready to toss it into the center of the swamp, when a tiny voice screamed, “No.”

“Who said that?” she asked, gazing into the trees.

There was nobody else around.

“Did you speak to me?” she asked the staff.

A voice whispered, “Yes.”

“You must be enchanted with human magic.”

She returned home, hoping to catch her husband before he left, but arrived to find a set of empty dishes. Petula set the staff down on the table and slumped into a chair, her eyes fixed on the enigmatic object. Before long, she drifted into a meditative trance.

“I’m here,” a gruff voice rumbled from far away. “Come closer.”

Petula rubbed her eyes, trying to see through a dense fog. She moved forward, drifting inches above the ground. At first she found herself in a forest of oaks and ironwoods, but as she moved, the trees thinned out and the land became hilly.

“I’ve never been out of the forest before,” she said, slowing down. “Must I keep going?”

“Don’t stop,” said the voice, sounding closer than before. “You’ve almost found me.”

After Petula passed the last of the trees, the grass disappeared and the hills turned into jagged rocks. She tried to change direction and return to the safety of the forest, but she couldn’t control her motion. She drifted above the rocky terrain until an iron cage appeared in the distance. The forbidding bars stretched from the ground to the sky, high enough to enclose the tallest trees. Inside the cage, a solitary figure sat patiently.

“Come closer,” said the human. “You have nothing to fear.”

Against her will, Petula floated forward, her unblinking eyes growing wider each second. She reached the cage and kept moving, passing through the solid iron bars and tumbling onto the rocks in front of the heavy-set human.

His head had been shaved to the scalp on one side, but his hair grew to shoulder length on the other. His face was compact, and battle scars covered his body. Beside him, an enormous broadsword was stuck blade-first in the ground.

“Greetings, Petula. My name is Oengus,” he said. “Thank you for rescuing me from this prison. I’ve been waiting far too long.”

Her heart thumped against her chest so hard that she saw its movement through her shirt. Once again, she tried to escape, but her legs refused to obey. She was trapped in the cage with the human.

“How do you know my name?” she asked. “We’ve never met.”

“You’re an Arboreal,” said Oengus, piercing her with his stare.

He yanked the sword from the ground and strolled forward. Petula remained motionless while Oengus passed first through her and then through the iron bars. Once outside the cage, he spun around to face her.

“The Ferfolk are to blame,” he shouted and raised his sword into the air. “We’ll destroy them all. No mercy!”

Petula gasped in her chair. She was still resting in her tree house and her husband hadn’t yet returned. The ebony staff, no longer on the table, lay across her lap. She tossed it against the far wall.

“You’re obviously cursed to bring such terrible visions,” she said, wrinkling her nose. “You should be returned to your swampy home. May you rot in the mud until you return to the soil.”

She crossed the room but stopped short of the black staff.

“I can’t do it,” she moaned, terrified of the evil human artifact.

Next Chapter